Block XY

Photography:

Khartoum

Revolution

Verena Schulthess

The North

Departure

North-East

Red Sea

Suakin – Sudan

Overnight, our ferry “MV RAHAL” of Namma Shipping Lines crosses the Red Sea towards Sudan. We have caught another storm front, but are sitting in our cabin in the dry. The MV RAHAL was built in Germany in 1972 and was then in service with Finnlines. At 47 years old, she is still providing the passenger and ro-ro service from Jeddah to Suakin. With a length of around 100 meters and a width of 17 meters, it is only about half the size of the large ferries from Italy to Greece. Sudanese people are sitting and lying everywhere. Very few people can afford one of the miserably narrow cabins. Our toilet is broken and stinks, there is no shower. Nevertheless, we have a good night behind us. But it will be a while before we arrive in Suakin. We are several hours late, as we can see from the position on our navigation device. They drove slowly because of the passengers, is the explanation – we think more because of the cargo, because the vehicles are not moored.

Entering the country is actually quite simple and takes a maximum of 2 hours. Our passports were taken from us on the ship and not returned. They are now at immigration. “But I don’t go to immigration without my passport – I don’t even know who has the passport”. After we have to pay some kind of “fee” (it was the bill of unloading) a ship’s officer accompanies us to immigration and helps us to find our passports. Ah, there they are, lying around in a little box with lots of paper.

Immigration clearance is quick. The stamp will soon be in your passport. But that costs money – but we haven’t had the opportunity to change money into Sudanese pounds yet. I give the customs officer a Saudi Ryal note – he changes it for us and then settles up with us in detail. Vehicle handling is another story. We have to drive up to a fenced-in area, but are not allowed in. A man dressed in white takes our carnet from us here and, as the people here all look the same to us, we somehow lose control. At some point, however, we are ushered into the customs yard. An officer looks at the inside of the vehicle out of interest and is satisfied. Now turn around and drive out again. Wait again. At last the necessary stamps are made and we have to pay the harbor tax at a wooden stall. The agent in white charges US$ 100 for his services. I protest and tell him that’s far too much for the price level here. Instead of the 370 Saudi ryal he asked for, I give him 275 ryal. Finally, he says that money isn’t everything, gets into his Mercedes “G” and drives off. And we also drive out of the harbor and, after falling over three times, turn right down to the water. Here, next to a canteen, there is a sandy spot right by the water that is very quiet.

Port Sudan

Although Port Sudan is the only large port in Sudan and is supposed to be a city of millions – the largest after Khartoum – we feel nothing of it. Port Sudan looks more like a provincial town. The millions of inhabitants probably live in the sparse dwellings on the outskirts of the city. This region is the tribal region of the Beja nomads. A month earlier, the Beja had massacred members of other tribes in the city, very bad things that I don’t want to write about here. Twenty-two people died and many were injured. But since the city is militarily secured, we feel safe in this city.

We have arrived in a completely different world. Truly Africa! In Port Sudan we buy a SIM card from MTN, change money (1 US$ = 80 pounds) and buy groceries. This takes time due to the heavy traffic. But we make it to the Sudan Red Sea Resort, 30 km outside the city, in the evening.

Sudan Red Sea Resort

Does the resort still exist? Everything we see from afar looks run-down. But, sure enough, we are greeted in a friendly manner by a young guy. We are allowed to camp here. At night we are alone with some pathetically howling dogs and cats. During the day, only a few visitors come to Pick Nick. We actually want to update our website here, but unfortunately we have no reception here with MTN. That’s why pictures are edited and laundry is washed. We can fill up with water directly from the cistern. Fortunately, we have a reserve system with us for filling in such situations, as no tap has the necessary pressure. And fortunately we have a water purification system on board. The groundskeeper offers a hotspot on his phone for writing emails.

Trip to Khartoum

Due to the lack of internet access, we decide to make our way to Khartoum. We manage the more than 750 km in two days despite the bad road in places. However, they are really exhausted afterwards. In front of Atbara, in the middle of the desert, hundreds of barrels of diesel – this is the home of the diesel black market.

After Atbara, there is one police checkpoint after another. Several times we experience that one of the policemen waves us through, but another stops us and wants us to pull over. But I refuse to pull over and am not prepared to pay any amount. If you’re standing on the side, it can take a long time and you’re at the mercy of the driver. I only follow the instructions at the military checkpoint. But they also behave very correctly and let us drive on immediately. Khartoum begins about 40 km before Khartoum. Traffic is becoming more demanding and denser. Lots of people on the road and vehicles close together. It’s a miracle that we make it to the Blue Nile Sayling Club, where we will be standing, without a scratch. But before that, the bridge over the Nile is closed. When we want to turn onto the next bridge, a policeman directs all the trucks in a different direction. As we are not familiar with the area, I insist on being able to drive over this bridge. After 5 minutes we are allowed to leave and reach the Sailing Club shortly after sunset. But before that, we have to drive under a bridge whose clearance is probably only 3 cm higher than our MAN. We’re glad we made it down there…not to mention the many trees whose branches we grazed….

Khartoum

Khartoum lies at the confluence of the White Nile, which flows from Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile, which flows from Ethiopia. The capital is home to a population of around 2.7 million people. The entire agglomeration with the cities of Ombdurman and Bahri (North Khartoum) is inhabited by over 8 million people.

The Blue Nile in the golden evening light. Confluence of the two Niles, white Nile on the left, blue Nile on the right.

Road traffic

If you drive into the city from Atbara, the first suburbs begin about 40 km before the city center. Although the access road has two lanes in each direction, as the right-hand lane is often used for parking and stopping, there is ultimately only more or less one lane available. The confusion of vehicles, tuk-tuks and pedestrians becomes complete in the area of markets and turnstiles that you pass through. It is often only a few centimeters from the side of our bumper to the next car body – on both sides. Even small cars try to push us trucks aside to get ahead faster and the proverbial friendliness of the Sudanese can sometimes turn into angry honking or shouting in traffic. Especially in the afternoon, when everyone wants to get home, the vehicles are parked all over the place and progress is sometimes measured in (somewhat exaggerated) centimeters.

Not enough effort in city traffic. Police officers can suddenly divert us from our planned route for reasons we don’t understand (but we then put up a fight). I also drove away from a policeman two or three times, as there is no signaling and their commands are often unfathomable for us – yes, and as a stranger you don’t know your way around the city.

Low-hanging tree branches are a problem, especially on the Nile, as are some bridges, where you have to measure the clearance height to make sure you don’t get stuck.

The worst, however, are open, deep shafts and channels, sometimes in the middle of the road or hard on the side of the road. So keep an eye open at all times, even as a pedestrian.

Diesel is not easy to come by. We also had to search and found a filling station that was “well-disposed” towards us, which sold us 100 liters once and 150 liters a second time. We are currently hoping to receive 200 liters for the onward journey to Ethiopia.

After driving through the city several times in our MAN to fill up with diesel and go shopping, we’ve got tired of it and have found a young, reputable cab driver who drives us around in a wonderful way and sets his prices fairly. Moueyd is his name and he is one of the wonderful people here in the country.

Emotional moments

We are standing in the parking lot of the “Blue Nile Sailing Club” – on the blue Nile, on the edge of the city center. We experience amazing emotional moments here and in the city.

Revolution Day

December 19, 2019 marked the first anniversary of the start of the revolution. As a counter-demonstration was announced for the following day, we moved our base to one of the churches in the city. However, the volume of traffic is already enormous and the military keeps diverting us. It takes us over two hours to cover a distance of 14 km – surrounded by people cheering and singing loudly. The whole town echoes the cheers. We are swept along, showing our enthusiasm by honking and waving. A truck loaded with young people slowly passes us, their cheers affecting us. They cheer loudly into the night:“Thank you Abdalla Hamdok (new prime minister), thanks to you such foreigners are now coming to us“!

Christmas

We weren’t even thinking about Christmas, let alone a festive Christmas. Just a few days before Christmas, the Sudanese government decided to December 25 as the official Christmas holiday. So far so good. On Christmas Eve, December 24th, we suddenly hear loud and clear orchestral Christmas music coming through the traffic from the Catholic church across the street. Throughout the evening, deep into the night, this music exudes a festive atmosphere around us. In the early morning of December 25, this music resounds again. The highlight was the mighty ringing of the bells that heralded Christmas Day. On this occasion, the raclette cheese was taken out of the freezer and of course prepared on the two-person candle stove. So we still had some unplanned Christmas and Christmas spirit.

Machine gun and bombs

It’s January 14. The MAN workshop in Khartoum is awesome. Very friendly and we have the impression that they also work professionally. But before the work begins, there is a 9 o’clock break. After a long wait, our mechanic appears again, but first with two large chicken sandwiches and drinks for us. We monitor the subsequent work as usual. So far so good.

Why are all the streets so congested? We finally turn into Nilstrasse and are surprised to see a massive police presence . What’s going on here? We park at our parking space at the Sailing Club and hear loud and clear

Machine gun chatter

. At first we think it’s another fireworks display or a wedding,

until we hear the first bombs detonate

.

In fact, there is fighting on the opposite bank of the Nile, not on television, but for real. From late afternoon until well into the night, machine guns and huge bomb detonations. We enquire with a friend and try to check our safety, but the people in charge of the Sailing Club are absent. The secret service organization of former President Bashir carried out an armed uprising, which fortunately was put down by the army that night.

Fighting took place at three different locations, on the opposite bank of the Nile and around the airport. All just a few kilometers from our location.

The Polyclinic

Behind high walls in one of the winding and inconspicuous alleyways is a small but excellent polyclinic, which is now run under the roof of the Episcopal Church. Many of the 150 to 200 patients who come here every day are internally displaced persons and victims of the civil wars in Darfur and South Sudan. They live far away on the outskirts of the city in mostly poor conditions. 2/3 of the patients are children and women.

The clinic was founded during the British occupation and continued to be run by the Swiss after the British left. In 2013, the regime at the time ordered the expulsion of the Swiss within a few days. The fact that the Polyclinic still exists today is partly due to the fact that a competent local management team was able to take up its work at this time.

We were allowed to visit the clinic in detail. Another highlight on our trip through Sudan.

We will provide further information on a separate page as soon as possible.

AbuRof Clinic Video Impressions

The North

A severe cold keeps us in Khartoum. On January 3, however, we have had enough and head north. We want to see more of Sudan. Our first destination is Old Dongola. To get there, we first have to cross the desert in wild weather. A strong and cold north wind is blowing. It constantly blows sand and dust over the landscape and the road and dries out the air even more than it already is.

Before Old Dongola, we cross the mighty NIL, which flows through the sandy desert, for the first time. Often accompanied on both sides by a more or less wide fertile belt, which provides the people here with a modest level of prosperity.

Old Dongola

Old Dongola was built around 500 AD. was founded as a fortress and soon developed into a fortified city with a strategically good location on the Nile. Until the invasion of the Arabs in the 13th century, who brought Islam to the country, Old Dongola was the capital of the Christian kingdom of Makuria, which extended as far as Atbara. Christianity was therefore already in the country around 800 years before Islam.

The field of ruins is extensive with only a few remains, interspersed with the ruins of a later Islamic settlement and an Islamic cemetery with its domed tombs. And of course it happens right here, we sink in, but manage to free ourselves in two attempts with the sand plates.

The most striking building is the “Throne Room”, a massive building on a rocky outcrop that has survived the centuries. From up here you can enjoy a beautiful view of the Nile and the adjacent palm gardens.

The first churches representing the Christian era were also excavated in Old Dongola. The “granite pillar church” was built in the 7th century over a previous church made of clay with solid granite. Fragments of other churches and multi-storey villas can be found on the site.

El Kurru

Petrified forest

If you turn off onto a dirt road towards the desert at El Kurru, about 8 km before Karima, you come to a petrified forest after about 3 km, which is slowly being exposed by erosion. We are surprised to find such a “dense” petrified forest in Sudan. The remnants of this “forest” fascinate us, also because of the (still) lonely location. Let’s hope it stays that way for a long time to come. In the light of the golden evening sun, we stroll through the area and see whole trunks peeking out of the surrounding gravel/sand. Here and there it seems as if someone has prepared logs for the winter. The absolute peace and quiet and the gentle whisper of the wind enhance the atmosphere. We are in our element and wonder what it must have looked like here when the area was still really wooded.

Graves

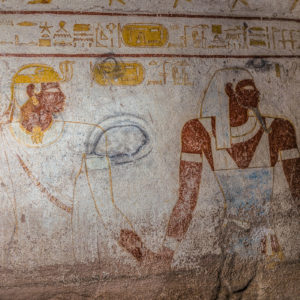

At El Kurru there are several graves of former rulers of the Nubian city of Napata. The oldest tombs are dated to around 860 BC. At that time, the construction of pyramids was not yet state of the art.

We are allowed to visit one of the tombs. You enter through a small opening at the front of a barrel-shaped vault and a steep staircase leads several meters down into the rock, where the burial chamber is located. Unfortunately, the lighting doesn’t work and we can only see the grave in the light of a flashlight. It is impressively painted and inscribed with hieroglyphics.

The other tombs are closed to tourists and the UNESCO cultural heritage is somewhat sparse.

Karima

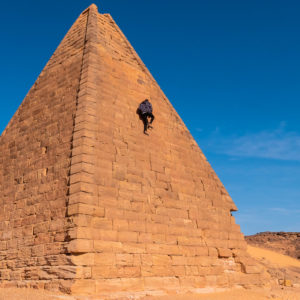

Mount Barkal and the pyramids

The *holy* mountain Barkal is visible from afar. At its foot lies a temple complex dedicated to the ancient god Amun. Also at the foot of the mountain is a pyramid complex typical of the land of “Kush”. The local rulers – the “Black Pharaohs” – extended their influence as far as Upper Egypt.

The pyramids trigger a natural fascination. Here we also meet a group of young Sudanese who later spontaneously invite us to “breakfast” the next morning via WhatsApp.

Visiting the aunt

The next day, we visit the Sudanese people we met at the pyramids for breakfast at 11am. Our MAN can show that it also fits into the narrow streets of a Sudanese village. The “breakfast” prepared by the aunt is more like lunch. The flatbread is dipped into the bean sauce with three fingers of the right hand, and the other vegetables, etc. are also picked up and put into the mouth in the same way. It tastes excellent. Time and again we are spontaneously invited to dinner, that’s how hospitable the people of Sudan are. Simply incredible, this spontaneous hospitality.

Later, we are accompanied on a stroll through the palm gardens to the Nile. We are allowed to see the “stables” inside a clay wall. A cow and her calf, some chickens, two donkeys and a few goats make up the farm’s stock.

An extremely peaceful atmosphere surrounds us and the greenery is good for our eyes after so much desert, sand and dust.

Atbara

From Karima to Atbara we drive 300 km through the Nubian desert. Fortunately, it is no longer as dusty and sandy as it was at the start of the journey. But the air is very dry and irritates the mucous membranes.

About 70 km before Atbara, we turn off at two ruins and drive down into a dry riverbed to spend the night here, sheltered from view. A lone shepherd – armed with an impressive knife – comes over to us, simply to greet us. The night is very quiet afterwards.

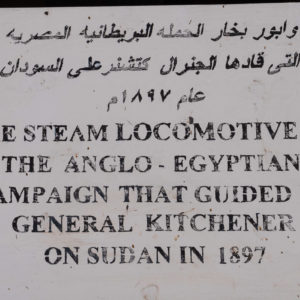

Atbara is the country’s railroad center with a huge station complex. There is supposed to be a railroad museum here. We can actually find the small museum in the former British Quarter. Admission is free of charge. The most valuable exhibit is the steam locomotive that secured supplies for the British from Egypt during the Anglo-Sudanese War. The railroad line from Wadi Halfa on the Egyptian border through the Nubian desert still exists, as does the line from Port Sudan and Khartoum to the Ethiopian border. Unfortunately, we don’t find anyone who can tell us whether we are allowed to take photos of the railroad facilities, so we leave it at the museum.

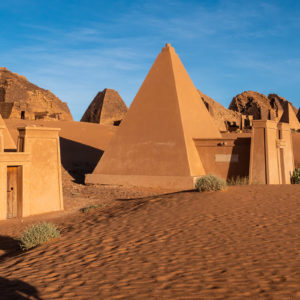

Meroe

We reach the Meroe pyramid field in the evening. But photography and filming is only possible to a limited extent. Groups of students populate the grounds and everyone wants to take a selfie with us. What the heck – these encounters are what make a trip to Sudan so appealing. Finally, school classes from a girls’ school flock to the pyramids. As always when they are in groups, the girls are exuberant and bursting with life. We end our visit, but enjoy the cheerfulness of these young people.

At sunrise we are back at the pyramids and see them in the golden sunlight. Apart from the camel riders, it is now quiet and we have time for sightseeing.

The Sudanese pyramids are smaller and steeper than the Egyptian pyramids, but far superior in number to those of Egypt. There are around 900 pyramids in the area around Meroe alone. They served as burial places for the kings, queens and high court officials of the Kushite Empire. The burial chambers are located under the pyramid and are no longer accessible. Some pyramids have a small mortuary temple in front of the pyramid with the typical H-front. They are between 10 and 30 meters high and run at an angle of 72°. It was built between 300 BC and 300 AD.

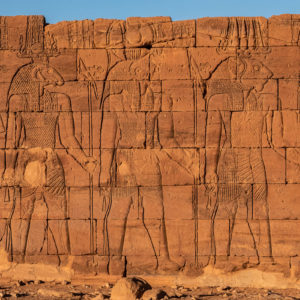

Naqa

Today we drive to the two temples of Naqa. A paved road leads into the desert and suddenly ends somewhere. With the help of a Sudanese guide, we find the right track and continue for about 20 km over mostly hard or then well-tracked soft sand.

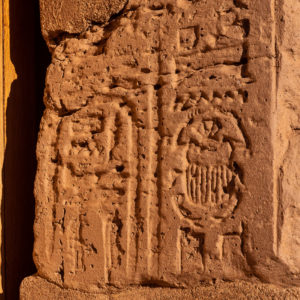

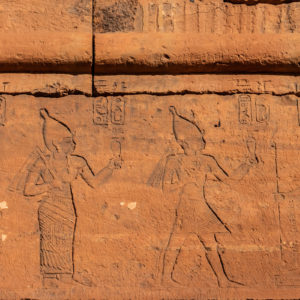

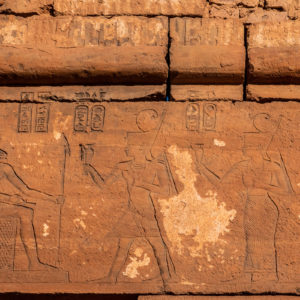

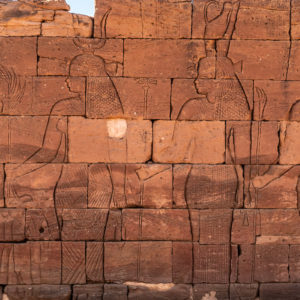

Who would have guessed that an advanced civilization like that of Egypt existed in Sudan from around 300 BC to 350 AD? The local rulers repeatedly put a lot of pressure on the Egyptian pharaohs. They also ruled Upper Egypt for a time and are known as the “Black Pharaohs”.

The temple complexes are witnesses of this Meroitic kingdom, the temple buildings show their own handwriting and are therefore not simply copied from those in Egypt.

We are delighted with the good condition of the temples and the secluded location. This gives us some idea of the cult of the time.

As the only visitors, “the buildings belong to us alone”. And once again it proves to be a good idea to stay overnight, as the Amun temple (above) is beautifully illuminated by the sun in the evening, while the Apedemak lion temple (below) is lit up early in the morning. Some of the figures at the Apedemak Temple have lion heads, hence the name “Lion Temple”. We enjoy the silence at night and being alone in this desert landscape does us good.

6 NIL Cataract

About 90 km northeast of Khartoum, the Nile flows through the 6th Nile Cataract, calculated from the Mediterranean. A place where it flows over some rocks. The first and second cataracts were flooded in the Nasser Reservoir in Egypt, the fourth cataract in the Karima Reservoir. The third, fifth (Atbara) and sixth cataracts still exist. So we visit the sixth and last cataract. In our imagination, we picture a tranquil natural spectacle. However, this cataract is an excursion destination for the locals with a corresponding infrastructure.

We are allowed to stay here overnight free of charge. Of course, we are expected to consume a fish from the Nile. What we do, but would no longer do today. It was only later that we realized that the freezer from which the fish had been taken had no electricity. The fish was also chopped up and deep-fried in oil with a breading …. We take the meal to our vehicle and eat there so that the Sudanese don’t see what we don’t eat, so as not to strain our stomachs. Gratefully, we realize that we have survived the meal without any side effects.

It was quiet during the night and this morning life begins in its original form. We have the Nile and the surrounding fields almost to ourselves and can observe how fields are still irrigated here with simple means (onions) using water from the Nile. Chickpeas are still being pressed into the small dams between the fields. A rural atmosphere now hangs over the landscape along the Nile.

Our journey continues from here back to Khartoum, where we plan to spend a few more days and then on to Ethiopia.

Block XY

After the 6th Nile cataract, we drive back to Khartoum, as the shortest route to Ethiopia is via the capital.

Khartoum and Omdurman are increasingly sprawling into the desert. This is where the internally displaced people settle. The conflicts in South Sudan and Darfour have left their mark. Due to the atrocities, many Sudanese have fled to the Khartoum region in the hope of a better life.

The settlements of the domestic refugees no longer have names but are designated with a block and a number. We visit the XY block.

The houses, always surrounded by a high wall, are made of dried bricks of sand and earth. The accommodation is very basic and has neither electricity nor water etc. The water is transported by busy donkey carts. The fact that diseases are prevalent here is solely due to the lack of infrastructure, which makes life difficult. Many of the patients of the polyclinic presented above come from such and similar settlements, 15 to 25 km and further away from the city center. A time-consuming route with a lack of and inadequate means of transportation, which can take up to 3 hours one way.

We’ve barely arrived in Block XY, barely unpacked the camera, and we’re already surrounded by a large crowd of children. Adorable little brats, dirty but cheerful and lively. Nevertheless, it is difficult to capture them on camera as they are either too close or all stand behind us to get a view of the camera monitor. We love these children and the people. They are so cheerful and friendly despite their hardship. They don’t beg and hold back.

Special Sudan

Who would have thought that there would be a small Christian church in the middle of block XY. In which other Muslim country is something like this possible (apart from Egypt and the Emirates)? Despite the repressive attitude of the former government, small Christian cells have survived.

Sick in Khartoum

On Saturday we get ready to leave for Ethiopia. But instead of driving through the city, we take a cab to the polyclinic we know. A doctor examines me. The lab report shows that I have a gastrointestinal infection. At least no malaria. Nauseous vomiting accompanied by diarrhea suddenly took hold of me in the morning. I need an injection to stop the vomiting. However, this is only available a day later , which means precious time is lost. All the water loss makes me very weak. But at least we can avoid the hospital, because at the last moment the medication starts to work and I can drink enough fluids again. I need a whole 2 1/2 weeks before I am reasonably fit to drive again.

During this time, our young cab driver Moueyd provides us with the essentials. He buys drinking water for us, brings bananas and changes money. Yes, indeed, we got to know many Sudanese as honest, open and helpful. If we miscounted in the flood of banknotes, the overpaid notes always came back automatically. A people who, in our view, deserve peace! And that brings us to our next topic: the Sudanese revolution from 2018 to 2019.

Sudanese revolution

The Sudanese pyramids and temples are witnesses to a bygone era – but the Sudanese Revolution is evidence of the present day.

Even under Omar Bashir’s tyranny, prices in the country tripled. Cash became scarce and corruption in the country increased. Women were endlessly disadvantaged and had hardly any basic rights. They could be arrested freely and then often had to pay money to be released.

Against this backdrop, demonstrations began in Atbara, Khartoum and other Sudanese cities on December 19, 2018, initially calling for economic reforms due to the rising cost of living, but soon demanding the resignation of President Omar al Bashir. Up to 70% of the demonstrators were women who were also fighting for their basic rights. The Sudanese Professionals Association was (and is) leading the fight.

The government violently suppressed the protests. On February 22, 2019, al-Bashir declared a state of emergency, dissolved the governments and replaced them with military and intelligence officials.

Mass protests broke out again on the weekend of April 6-7, 2019, and on April 11, 2019, al-Bashir was removed from office by the military.

Despite the coup, the protests continued with demands for the military to make way for a civilian transitional government. The negotiations came to a halt on June 3, 2019 when the

Rapid Support Forces

at the

Khartoum massacre

killed 118 people and injured and raped many more

.

In response to the Khartoum massacre and the subsequent arrests, opposition groups called for a general strike from June 9-11. They called on the population to engage in civil disobedience and non-violent protest.

On July 5, 2019, an agreement was reached between the opposition and the military council and both sides signed a corresponding agreement on July 17, 2019. It provides for a “Sovereign Council” made up of representatives of the military and the protest movement, initially chaired by the army and later by the opposition.

We ask Moueyd, our cab driver, to take us to the revolutionary squares. It takes us from the Blue Nile Bridge to Nile Street (15.612011, 32.544104). Here, many of the people who lost their lives during the revolution are painted on a wall.228 people are said to have died in total, 118 of whom died in the Khartoum massacre of June 3, 2019 alone. Many of the bodies were simply thrown into the Nile and “disposed of” in such an undignified manner.

3 million Sudanese were peacefully demonstrating in these streets on June 3, 2019, when they were fired upon by the Super Rapid Forces from a vacant building that was still under construction. Soldiers from the regular army had mingled with the people to protect them.

Today, the “fight” is not yet over. The old regime, or what is left of it, is steering with a cold wind against democratic achievements. Diesel was deliberately withdrawn and is being hoarded, the bus drivers of the new city buses are being paid NOT to drive, and much more. In the meantime, an assassination attempt was also made against the current Prime Minister, fortunately without consequences, etc.

We hope that the people with the friendly smiles and endless hospitality will continue to make progress and that democratic development can be maintained and consolidated.

Departure

On February 4, 2020, about 3 weeks “late”, we finally set off for Ethiopia. First we drive to “our” filling station to fill up – and we get the 200 liters of diesel we want without hesitation. Sadek, the man in charge, had given us his phone number beforehand and so we were able to make sure that Diesel was there via WhatsApp.

It is about 600 km from Khartoum to the Ethiopian border. We estimate 3 days for the trip. On the one hand because I don’t feel 100% yet, on the other hand because we heard that the last 80 km were in terrible condition.

We spend the first night on the Nile, close to a police checkpoint. Yes, and we made the mistake of taking a dirt road to the Nile before the police checkpoint. As soon as we arrive at our idyllic spot, two policemen stop by and check us. They want a selfie with us and the MAN and then drive off. But one of them comes back. His boss wanted to see us and we had to drive to the next village. We could spend the night there. We refuse and tell him that we won’t be going anywhere today as the sun is about to set and we don’t want to drive at night. Finally, we hand him a copy of our passports and visas. This satisfies him and the rest of the night remains quiet. It has to be said that the policeman didn’t like what his boss was asking us to do.

There is not really much to report about the onward journey to the Ethiopian border, except that it is getting drier, that we are only slowly gaining altitude, that cotton is cultivated and that we spend the night undisturbed at the edge of a field before El Qadarif.

The route from El Qadarif to the border is indeed almost unreasonable over a distance of around 70 to 80 km. However, all border traffic with Ethiopia runs along this road. More pothole than road and so wonderfully spread out that you often have to drive through them. This means braking, downshifting and upshifting X times. A few kilometers before the border we find a small quarry to spend the night.

Early in the morning of February 7, 2020, we drive the last few kilometers to the border at Metemma. Leaving Sudan is easy thanks to coordinates from iOverlander. The border guards are very friendly and uncomplicated.

Goodbye Sudan, we spent almost exactly two months in Sudan. For us, this was one of the highlights of our trip to Cape Town.

The Ethiopian side is correct and friendly and reserved. Entry is quick, only the registration of the vehicle and the subsequent somewhat meticulous checks take time. So it’s lunchtime before we can cross the border.

Suchen und Finden

Recent Comments

- AL Hampton on BERG SINAI in Arabia

- нαssαи on Administrative vehicle

- Ben Cooper on Hizma Desert and Al-Shaq Gorge

- Dorothy chao on Caves of the Jethro

- Ben on Mushroom Rock and Wadi Disah

- Ben on Via Riyadh to Ha’il

- Ben on Emirates

- Ben on Saudi Arabia East

- Ben Cooper on Dascht-e Lut – Desert Lut

- Ben Cooper on Cosmopolitan city of Isfahan

Jetzt Kontakt aufnehmen

Newsletter anmelden!

Jetzt für Newsletter registrieren!

Bleibe mit uns in Kontakt und erhalte monatlich unsere News zugestellt.

3 Comments. Leave new

Thanks for your detailed website. Planning our Overland journey and this crossing between Sudan and Saudi Arabia was really an unknown situation for us before your post! Thanks once more, still reading your posts! Keep going! Right now our rig is stucked in Canada.

These are brilliant I have travelled to Sudan with my Sudanese husband..I see a photo of a Massey fugson tractor which he imports wonder if that is one if his ..amazing place

What a fantastic journey. So much history. You are just ahead of the Corona Virus. Safe travels.